Hydrogen atom

| Hydrogen-1 | |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Name, symbol | protium, 1H |

| Neutrons | 0 |

| Protons | 1 |

| Nuclide Data | |

| Natural abundance | 99.985% |

| Half-life | Stable |

| Isotope mass | 1.007825 u |

| Spin | ½+ |

| Excess energy | 7,288.969±0.001 keV |

| Binding energy | 0±0 keV |

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral atom contains a single positively-charged proton and a single negatively-charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb force. The most abundant isotope, hydrogen-1, protium, or light hydrogen, contains no neutrons; other isotopes of hydrogen, such as deuterium, contain one or more neutrons. The formulas below are valid for all three isotopes of hydrogen, however slightly different values of the Rydberg constant (correction formula given below) must be used for each hydrogen isotope.

The hydrogen atom has special significance in quantum mechanics and quantum field theory as a simple two-body problem physical system which has yielded many simple analytical solutions in closed-form.

In 1914, Niels Bohr obtained the spectral frequencies of the hydrogen atom after making a number of simplifying assumptions. These assumptions, the cornerstones of the Bohr model, were not fully correct but did yield the correct energy answers. Bohr's results for the frequencies and underlying energy values were confirmed by the full quantum-mechanical analysis which uses the Schrödinger equation, as was shown in 1925–1926. The solution to the Schrödinger equation for hydrogen is analytical. From this, the hydrogen energy levels and thus the frequencies of the hydrogen spectral lines can be calculated. The solution of the Schrödinger equation goes much further than the Bohr model however, because it also yields the shape of the electron's wave function ("orbital") for the various possible quantum-mechanical states, thus explaining the anisotropic character of atomic bonds.

The Schrödinger equation also applies to more complicated atoms and molecules. However, in most such cases the solution is not analytical and either computer calculations are necessary or simplifying assumptions must be made.

Contents |

Solution of Schrödinger equation: Overview of results

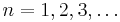

The solution of the Schrödinger equation (wave equations) for the hydrogen atom uses the fact that the Coulomb potential produced by the nucleus is isotropic (it is radially symmetric in space and only depends on the distance to the nucleus). Although the resulting energy eigenfunctions (the orbitals) are not necessarily isotropic themselves, their dependence on the angular coordinates follows completely generally from this isotropy of the underlying potential: The eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (that is, the energy eigenstates) can be chosen as simultaneous eigenstates of the angular momentum operator. This corresponds to the fact that angular momentum is conserved in the orbital motion of the electron around the nucleus. Therefore, the energy eigenstates may be classified by two angular momentum quantum numbers, ℓ and m (both are integers). The angular momentum quantum number ℓ = 0, 1, 2, ... determines the magnitude of the angular momentum. The magnetic quantum number m = −ℓ, ..., +ℓ determines the projection of the angular momentum on the (arbitrarily chosen) z-axis.

In addition to mathematical expressions for total angular momentum and angular momentum projection of wavefunctions, an expression for the radial dependence of the wave functions must be found. It is only here that the details of the 1/r Coulomb potential enter (leading to Laguerre polynomials in r). This leads to a third quantum number, the principal quantum number n = 1, 2, 3, .... The principal quantum number in hydrogen is related to atom's total energy.

Note that the maximum value of the angular momentum quantum number is limited by the principal quantum number: it can run only up to n − 1, i.e. ℓ = 0, 1, ..., n − 1.

Due to angular momentum conservation, states of the same ℓ but different m have the same energy (this holds for all problems with rotational symmetry). In addition, for the hydrogen atom, states of the same n but different ℓ are also degenerate (i.e. they have the same energy). However, this is a specific property of hydrogen and is no longer true for more complicated atoms which have a (effective) potential differing from the form 1/r (due to the presence of the inner electrons shielding the nucleus potential).

Taking into account the spin of the electron adds a last quantum number, the projection of the electron's spin angular momentum along the z-axis, which can take on two values. Therefore, any eigenstate of the electron in the hydrogen atom is described fully by four quantum numbers. According to the usual rules of quantum mechanics, the actual state of the electron may be any superposition of these states. This explains also why the choice of z-axis for the directional quantization of the angular momentum vector is immaterial: an orbital of given ℓ and m′ obtained for another preferred axis z′ can always be represented as a suitable superposition of the various states of different m (but same l) that have been obtained for z.

Alternatives to the Schrödinger Theory

In the language of Heisenberg's Matrix Mechanics, the hydrogen atom was first solved by Wolfgang Pauli[1] using a rotational symmetry in four dimension [O(4)-symmetry] generated by the angular momentum and the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector. By extending the symmetry group O(4) to the dynamical group O(4,2), the entire spectrum and all transitions were embedded in a single irreducible group representation.[2]

In 1979 the (non relativistic) hydrogen atom was solved for the first time within Feynman's path integral formulation of quantum mechanics.[3][4] This work greatly extended the range of applicability of Feynman's method.

Mathematical summary of eigenstates of hydrogen atom

Energy levels

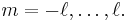

The energy levels of hydrogen, including fine structure, are given by

where α is the fine-structure constant and j is a number which is the total angular momentum eigenvalue; that is, ℓ ± 1/2 depending on the direction of the electron spin. The quantity in square brackets arises from relativistic (spin-orbit) coupling interactions (as further described below in the section entitled "Features going beyond the Schrödinger solution").

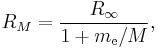

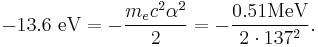

The value of 13.6 eV is called the Rydberg constant and can be found from the Bohr model, and is given by

where me is the mass of the electron, qe is the charge of the electron, h is the Planck constant, and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity.

The Rydberg constant is connected to the fine-structure constant by the relation

This constant is often used in atomic physics in the form of the Rydberg unit of energy:

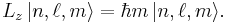

The exact value of the Rydberg constant above assumes that the nucleus is infinitely massive with respect to the electron. For hydrogen-1, hydrogen-2 (deuterium), and hydrogen-3 (tritium) the constant must be slight modified to use the reduced mass of the system, rather than simply the mass of the electron. However, since the nucleus is much heavier than the electron, the values are nearly the same. The Rydberg constant RM for a hydrogen atom (one electron), R is given by : where

where  is the rest mass of the electron, and M is the mass of the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen-1, the quantity

is the rest mass of the electron, and M is the mass of the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen-1, the quantity  is about 1/1836, reflecting the ratio electron to proton mass. For deuterium and tritium, the numbers are about 1/3670 and 1/5497 respectively. These figures, when added to 1 in the denominator, represent very small corrections in the value of R, and thus only small corrections to all energy levels in corresponding hydrogen isotopes.

is about 1/1836, reflecting the ratio electron to proton mass. For deuterium and tritium, the numbers are about 1/3670 and 1/5497 respectively. These figures, when added to 1 in the denominator, represent very small corrections in the value of R, and thus only small corrections to all energy levels in corresponding hydrogen isotopes.

Wavefunction

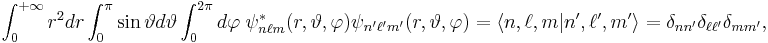

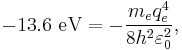

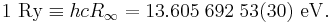

The normalized position wavefunctions, given in spherical coordinates are:[6]

where:

,

, is the Bohr radius,

is the Bohr radius, are the generalized Laguerre polynomials of degree n − ℓ − 1, and

are the generalized Laguerre polynomials of degree n − ℓ − 1, and is a spherical harmonic function of degree ℓ and order m. Note that the generalized Laguerre polynomials are defined differently by different authors. The usage here is consistent with the definitions used by Messiah[7] and Griffiths.[8] But not Mathematica where it differs by a factor of

is a spherical harmonic function of degree ℓ and order m. Note that the generalized Laguerre polynomials are defined differently by different authors. The usage here is consistent with the definitions used by Messiah[7] and Griffiths.[8] But not Mathematica where it differs by a factor of  [9] In other places,[10] the Generalized Laguerre polynomial appearing in the Hydrogen wave function may be

[9] In other places,[10] the Generalized Laguerre polynomial appearing in the Hydrogen wave function may be  .

.

The quantum numbers can take the following values:

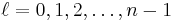

Additionally, these wavefunctions are normalized (i.e., the integral of their modulus square equals 1) and orthogonal:

where  is the representation of the wavefunction

is the representation of the wavefunction  in Dirac notation, and

in Dirac notation, and  is the Kronecker delta function.[11]

is the Kronecker delta function.[11]

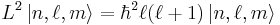

Angular momentum

The eigenvalues for Angular momentum operator:

Visualizing the hydrogen electron orbitals

The image to the right shows the first few hydrogen atom orbitals (energy eigenfunctions). These are cross-sections of the probability density that are color-coded (black represents zero density and white represents the highest density). The angular momentum (orbital) quantum number ℓ is denoted in each column, using the usual spectroscopic letter code (s means ℓ = 0, p means ℓ = 1, d means ℓ = 2). The main (principal) quantum number n (= 1, 2, 3, ...) is marked to the right of each row. For all pictures the magnetic quantum number m has been set to 0, and the cross-sectional plane is the xz-plane (z is the vertical axis). The probability density in three-dimensional space is obtained by rotating the one shown here around the z-axis.

The "ground state", i.e. the state of lowest energy, in which the electron is usually found, is the first one, the 1s state (principal quantum level n = 1, ℓ = 0).

An image with more orbitals is also available (up to higher numbers n and ℓ).

Black lines occur in each but the first orbital: these are the nodes of the wavefunction, i.e. where the probability density is zero. (More precisely, the nodes are Spherical harmonics that appear as a result of solving Schrödinger's equation in polar coordinates.)

The quantum numbers determine the layout of these nodes.[12] There are:

total nodes,

total nodes, of which are angular nodes:

of which are angular nodes:

angular nodes go around the

angular nodes go around the  axis (in the xy plane). (The figure above does not show these nodes since it plots cross-sections through the xz-plane.)

axis (in the xy plane). (The figure above does not show these nodes since it plots cross-sections through the xz-plane.) (the remaining angular nodes) occur on the

(the remaining angular nodes) occur on the  (vertical) axis.

(vertical) axis.

(the remaining non-angular nodes) are radial nodes.

(the remaining non-angular nodes) are radial nodes.

Features going beyond the Schrödinger solution

There are several important effects that are neglected by the Schrödinger equation and which are responsible for certain small but measurable deviations of the real spectral lines from the predicted ones:

- Although the mean speed of the electron in hydrogen is only 1/137th of the speed of light, many modern experiments are sufficiently precise that a complete theoretical explanation requires a fully relativistic treatment of the problem. A relativistic treatment results in a momentum increase of about one part in 37,000 for the electron. Since the electron's wavelength is determined by its momentum, orbitals containing higher speed electrons show contraction due to smaller wavelengths.

- Even when there is no external magnetic field, in the inertial frame of the moving electron, the electromagnetic field of the nucleus has a magnetic component. The spin of the electron has an associated magnetic moment which interacts with this magnetic field. This effect is also explained by special relativity, and it leads to the so-called spin-orbit coupling, i.e., an interaction between the electron's orbital motion around the nucleus, and its spin.

Both of these features (and more) are incorporated in the relativistic Dirac equation, with predictions that come still closer to experiment. Again the Dirac equation may be solved analytically in the special case of a two-body system, such as the hydrogen atom. The resulting solution quantum states now must be classified by the total angular momentum number j (arising through the coupling between electron spin and orbital angular momentum). States of the same j and the same n are still degenerate.

- There are always vacuum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, according to quantum mechanics. Due to such fluctuations degeneracy between states of the same j but different l is lifted, giving them slightly different energies. This has been demonstrated in the famous Lamb-Retherford experiment and was the starting point for the development of the theory of Quantum electrodynamics (which is able to deal with these vacuum fluctuations and employs the famous Feynman diagrams for approximations using perturbation theory). This effect is now called Lamb shift.

For these developments, it was essential that the solution of the Dirac equation for the hydrogen atom could be worked out exactly, such that any experimentally observed deviation had to be taken seriously as a signal of failure of the theory.

Due to the high precision of the theory also very high precision for the experiments is needed, which utilize a frequency comb.

Hydrogen ion

Hydrogen is not found without its electron in ordinary chemistry (room temperatures and pressures), as ionized hydrogen is highly chemically reactive. When ionized hydrogen is written as "H+" as in the solvation of classical acids such hydrochloric acid, the hydronium ion, H3O+, is meant, not a literal ionized single hydrogen atom. In that case, the acid transfers the proton to H2O to form H3O+.

Ionized hydrogen without its electron, or free protons, are common in the interstellar medium, and solar wind.

See also

| Book: Hydrogen | |

| Wikipedia books are collections of articles that can be downloaded or ordered in print. | |

References

- ^ Pauli, W (1926). "Über das Wasserstoffspektrum vom Standpunkt der neuen Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik 36: 336–363. Bibcode 1926ZPhy...36..336P. doi:10.1007/BF01450175.

- ^ Kleinert H. (1968). "Group Dynamics of the Hydrogen Atom". Lectures in Theoretical Physics, edited by W.E. Brittin and A.O. Barut, Gordon and Breach, N.Y. 1968: 427–482. http://www.physik.fu-berlin.de/~kleinert/kleiner_re4/4.pdf.

- ^ Duru I.H., Kleinert H. (1979). "Solution of the path integral for the H-atom". Physics Letters B 84 (2): 185–188. Bibcode 1979PhLB...84..185D. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(79)90280-6. http://www.physik.fu-berlin.de/~kleinert/kleiner_re65/65.pdf.

- ^ Duru I.H., Kleinert H. (1982). "Quantum Mechanics of H-Atom from Path Integrals". Fortschr. Phys 30 (2): 401–435. doi:10.1002/prop.19820300802. http://www.physik.fu-berlin.de/~kleinert/kleiner_re83/83.pdf.

- ^ P.J. Mohr, B.N. Taylor, and D.B. Newell (2011), "The 2010 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" (Web Version 6.0). This database was developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. Available: http://physics.nist.gov/constants. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899. Link to R∞, Link to hcR∞

- ^ David Griffiths (2008). Introduction to elementary particles. Wiley-VCH. pp. 162–. ISBN 9783527406012. http://books.google.com/books?id=w9Dz56myXm8C&pg=PA162. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ Messiah, Albert (1999). Quantum Mechanics. New York: Dover. pp. 1136. ISBN 0-486-40924-4.

- ^ Griffiths, David (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.. pp. 152. ISBN 0131118927.

- ^ LaguerreL. Wolfram Mathematica page

- ^ Condon and Shortley (1963). The Theory of Atomic Spectra. London: Cambridge. pp. 441.

- ^ Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, Griffiths 4.89

- ^ Summary of atomic quantum numbers. Lecture notes. 28 July 2006

Books

- Griffiths, David J. (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-111892-7. Section 4.2 deals with the hydrogen atom specifically, but all of Chapter 4 is relevant.

- Bransden, B.H.; C.J. Joachain (1983). Physics of Atoms and Molecules. Longman. ISBN 0-582-44401-2 tacos.

- Kleinert, H. (2009). Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, 4th edition, Worldscibooks.com, World Scientific, Singapore (also available online physik.fu-berlin.de)

External links

- Physics of hydrogen atom on Scienceworld

- Interactive graphical representation of orbitals

- Applet which allows viewing of all sorts of hydrogenic orbitals

- The Hydrogen Atom: Wave Functions, and Probability Density "pictures"

- Basic Quantum Mechanics of the Hydrogen Atom

- "Research team takes image of hydrogen atom" Kyodo News, Friday, November 5, 2010 – (includes image)

| Lighter: (none, lightest possible) |

Hydrogen atom is an isotope of hydrogen |

Heavier: hydrogen-2 |

| Decay product of: neutronium-1 helium-2 |

Decay chain of Hydrogen atom |

Decays to: Stable |

![E_{jn} = \frac{-13.6 \ \mathrm{eV}}{n^2} \left[1 %2B \frac{\alpha^2}{n^2}\left(\frac{n}{j%2B\frac{1}{2}} - \frac{3}{4} \right) \right] ,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ca853501ebae63f540a635e63b1e9a88.png)

![\psi_{n\ell m}(r,\vartheta,\varphi) = \sqrt {{\left ( \frac{2}{n a_0} \right )}^3\frac{(n-\ell-1)!}{2n[(n%2B\ell)!]^3} } e^{- \rho / 2} \rho^{\ell} L_{n-\ell-1}^{2\ell%2B1}(\rho) \cdot Y_{\ell}^{m}(\vartheta, \varphi )](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b5f4b324f1a1868efa8c6189df0c1184.png)